How LinkedIn

Got Their First Users

LinkedIn is a professional social networking service platform for the business community. Founded in 2003 (Mountain View, CA).

The LinkedIn growth story is one of the most educational ones because it provides a clear example of successful startup fostering, based on pure marketing (growth hacking) rather than on the product itself. The 80/20 MPF, localized targeting, public profiles SEO, aggressive email lists exploiting, double viral loop, delayed monetization and strength prioritizing; these are the seven most significant growth hacks that LinkedIn has been using since the beginning. These golden seven must-knows are as elegant as they are useful.

The LinkedIn concept was established at the end of 2002 when Reid Hoffman gathered a team of old SocialNet and PayPal colleagues to work on a new startup. As it is true for many leading startups nowadays, LinkedIn was rooted on the "80/20 MPF" (Market/Product Fit) growth hack designed to get the first traction ASAP and with minimal risk. That first growth hack ("80/20 MPF") implies coping another product that is already at Product/Market Fit stage and has enough market adoption. Though that kind of coping suggests you keep the fundamentals of a product the same (80%) while substantially reinventing 20% of it.

As a pattern of reproduction, Hoffman created the Six Degrees social network, named after the six degrees of separation concept whereby all living people are six or fewer steps away from each other. Imagine every chain of "a friend of a friend" statements can be made to connect any two people in a maximum of six steps and there you have the six degrees of separation. Six Degrees, the social network, was a place where you could connect with friends, but you could only post textual messages with no photos or video. The company was sold in 1999 (after reaching 3.5 million users since 1996) and died a year after in the Dot-Com Crash being unable to manage growth and suffering from petty retention. Hoffman took 80% of Six Degrees’ fundamentals and acquired its patent.

From that, LinkedIn was born, a network that allowed professionals to find each other and connect. As for the product’s 20% reinvention, Hoffman and team decided to set focus on lasting engagement, open identity, and connections.

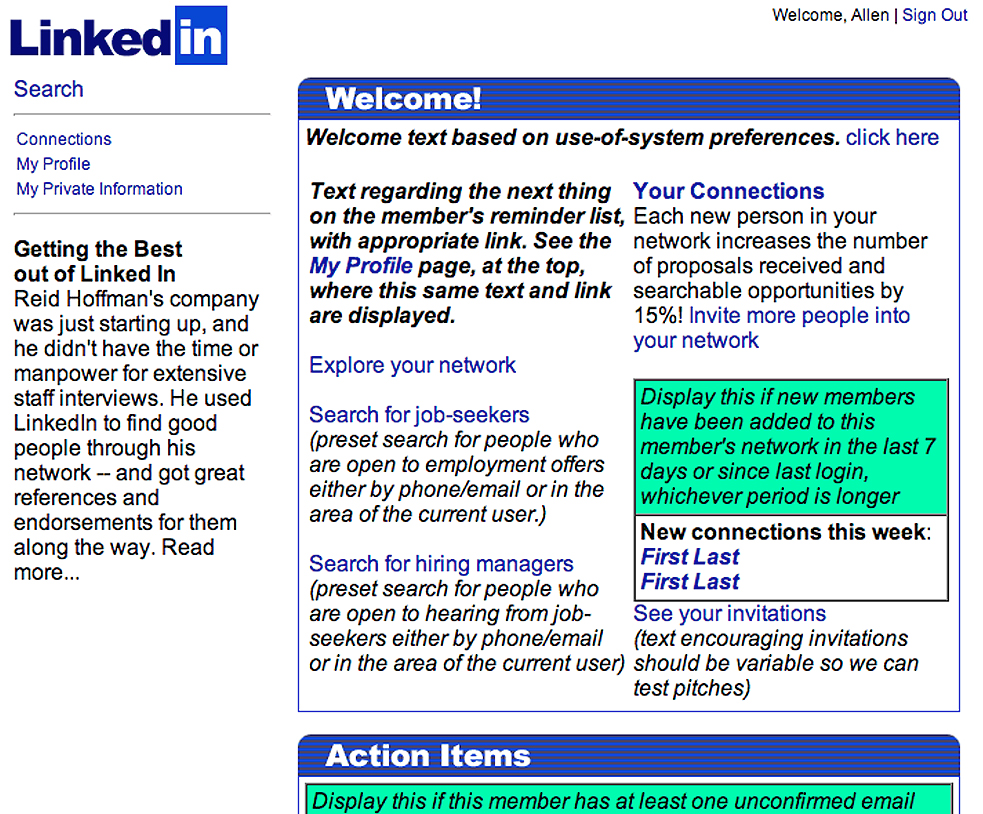

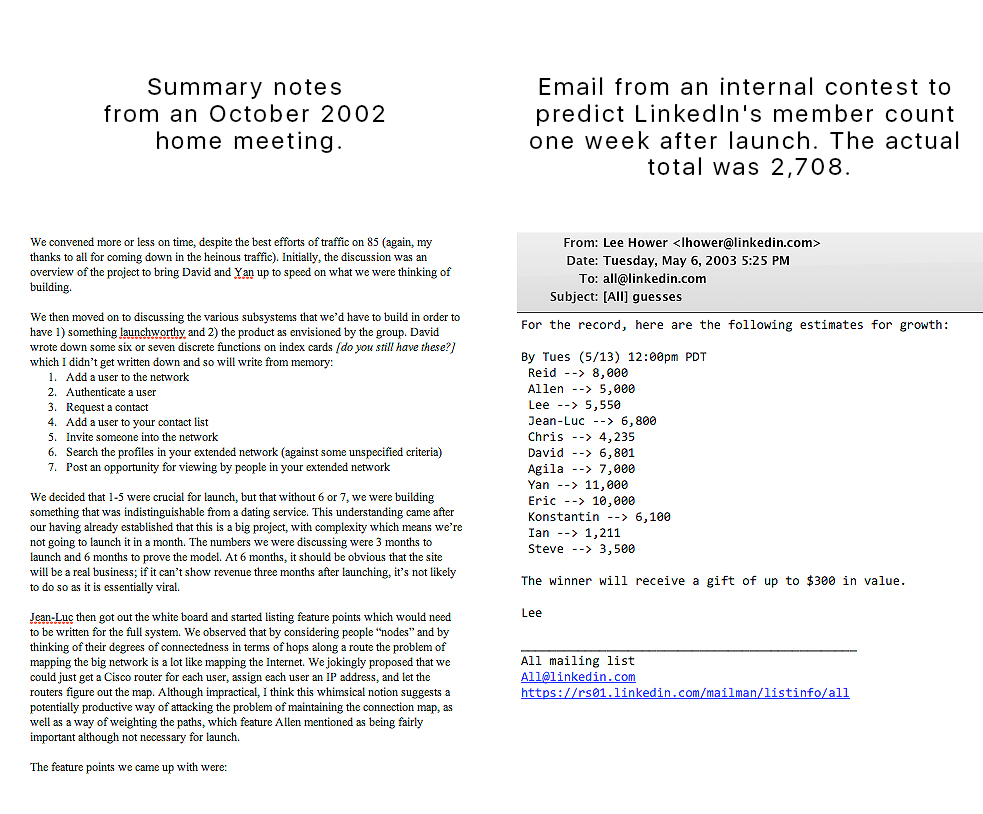

In May 2003, just six months after the start of development, LinkedIn officially launched. To make sure the systems worked, the 13 people associated with the company invited just 112 people and started growing from there. Some days there were as few as twenty signups. Eventually, the second growth hack - growing connections - entered the game and helped LinkedIn to reach 12k users in just one week.

The startup, however, would need more than that to gain real traction. The problem was the initial resistance to the core concept of LinkedIn by users and venture capital (VC). When the site launched in 2003, the typical reaction to LinkedIn was something like, "Teenagers friending each other and trading pictures on social networks - sure! You want grownup professionals to friend each other over the web? That won’t work." VC was as pessimistic as pragmatic: they expected that, even if it did work, Friendster (the most popular network at the time) would add a business section to the site and LinkedIn would be dead. Bloggers hated the idea of separating their private and professional lives in two and posted with enthusiastic disdain about LinkedIn.

Despite these challenges, LinkedIn was stacking their growth hacking strategy when early traction was worse than anticipated. The second growth hack that made a difference for the young social network was localized targeting on a specific community and place. Hoffman decided to focus first on the Silicon Valley tech scene by having the founders invite only the professional IT-connections they had amassed in and around Silicon Valley.

Moreover, that growth doubled when Hoffman decided to invite only successful friends and connections, recognizing that cultivating an aspirational brand was crucial to drive mainstream adoption. The local critical mass that breeds both user loyalty and word of mouth (virality) was met within the following four months.

Having the power players of Silicon Valley’s dot-com successes on the network increased the appeal of LinkedIn, making it a must-have for up-and-coming Valley workers who wanted to connect with potential investors and advisors. CNET was one of the first to give the company a glowing review and others followed. As a result, one year after launching, LinkedIn reached 500,000 users.

To keep the growth soaring even more, in 2004 the company resorted to their third growth hack in their history: aggressive email list exploiting. This particular growth hack, it must be mentioned, is very controversial. Such scales solicitations worked for LinkedIn (probably, due to the pioneer-effect), though it burned a lot of other ensuing startups that applied it later.

LinkedIn began exploiting the concept of contact importing, something that’s commonplace now but was pretty novel in 2004. At this point, the concept of typing in your email and password and letting a website sift through your contacts was new and most people didn’t even have connections in their webmail clients. To account for these challenges, LinkedIn built an Outlook plugin for users to install that would mine their Outlook contacts for them.

After that, the company began to overt to those contacts acquired through emails using email-marketing gimmicks that are classic today. For example, they discovered it took a benchmark of four letters before the average target user made his mind to register on a platform. Furthermore, the seemingly "throwaway" line at the end of the LinkedIn invitation copy below was shown to result in more invites sent by new users: "So I found you while I was looking around the network. Let’s connect directly; I’m happy to help you with requests and forward things incoming. It will probably make both of our networks bigger." It was shown to result in even more invites sent out by new users.

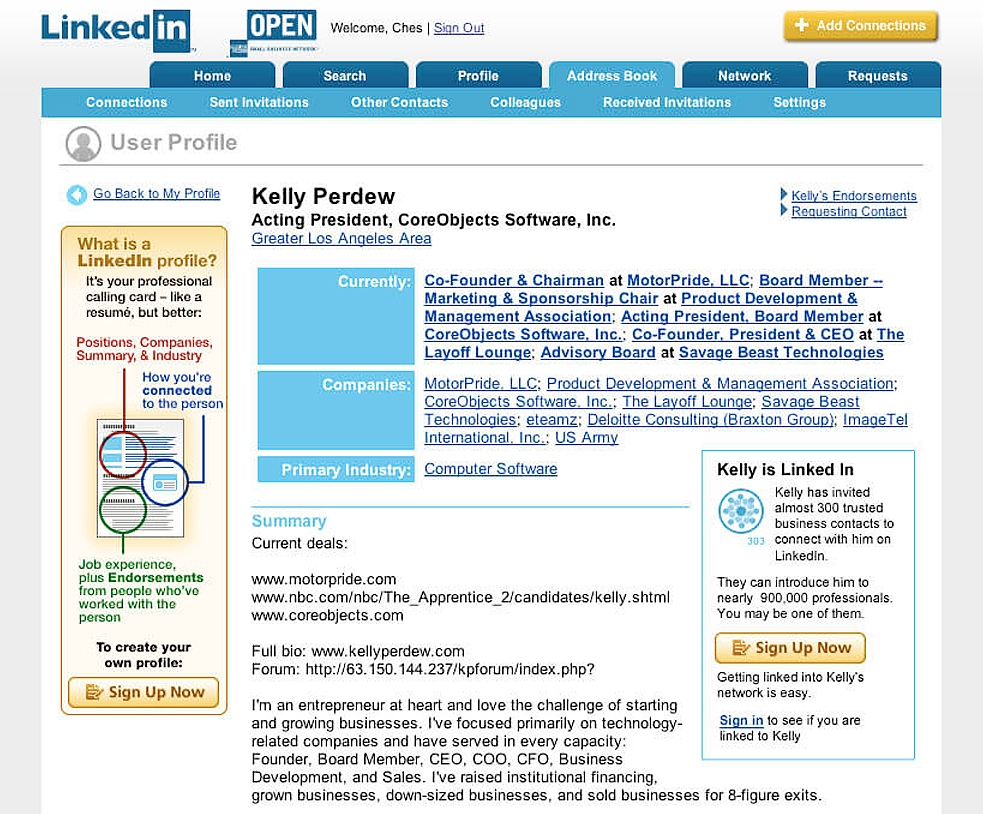

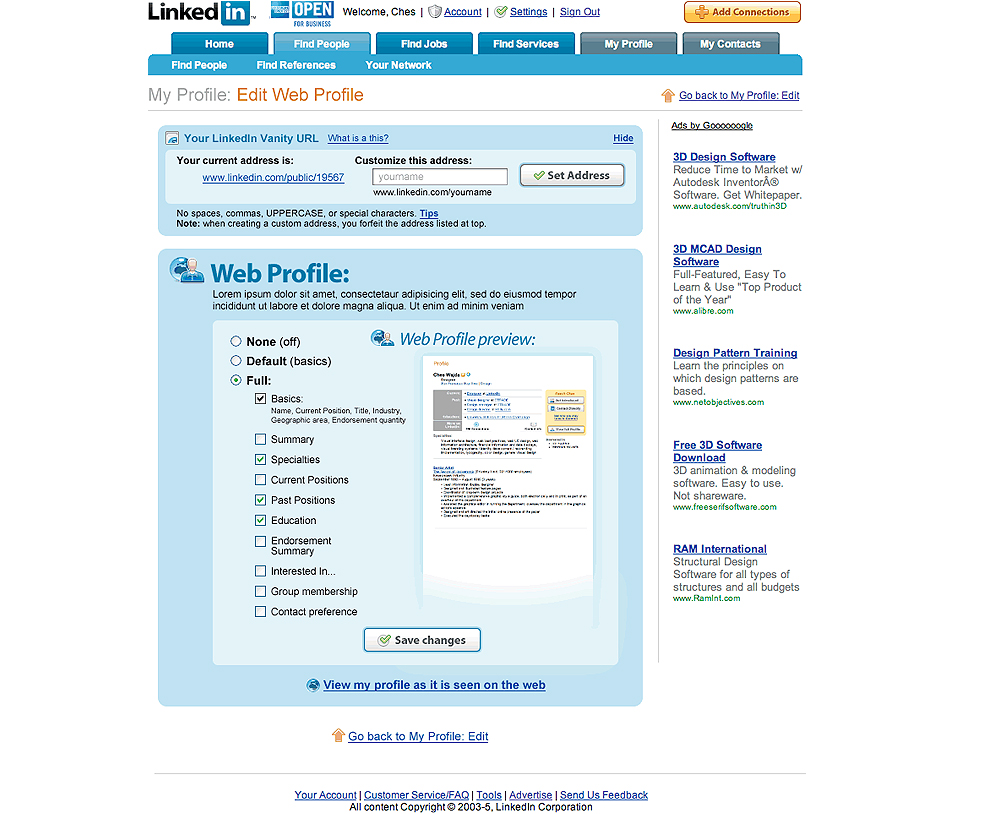

In 2006, after LinkedIn reached its critical two million users, the company debuted their fourth pivotal growth hack: public profiles SEO (Search Engine Optimization). It might sound weird now, but before LinkedIn made user profiles public, it was exceedingly unlikely for real people to show up in organic search results. By making profiles public, LinkedIn created more traffic and user acquisition gains. Profiles started showing up in search results, putting LinkedIn in front of more and more people. Once people clicked into the site from a search engine, they had to then sign up for LinkedIn before they could connect with people through filtered searches. The site’s natural weight in Google results put user profiles quickly at the top of results for name-based searches in Google.

The decision to bring that growth hack to life was based on the early users’ feedback as well as the first pivot related to it. The company’s original assumption was that LinkedIn would be used primarily to search for and make new connections through searching titles, skills and referrals, not names. As it turned out, however, people tried to use LinkedIn to make new acquaintances in person and keep in touch with established ones based on names, so the company modified the site’s search function to work with that trend.

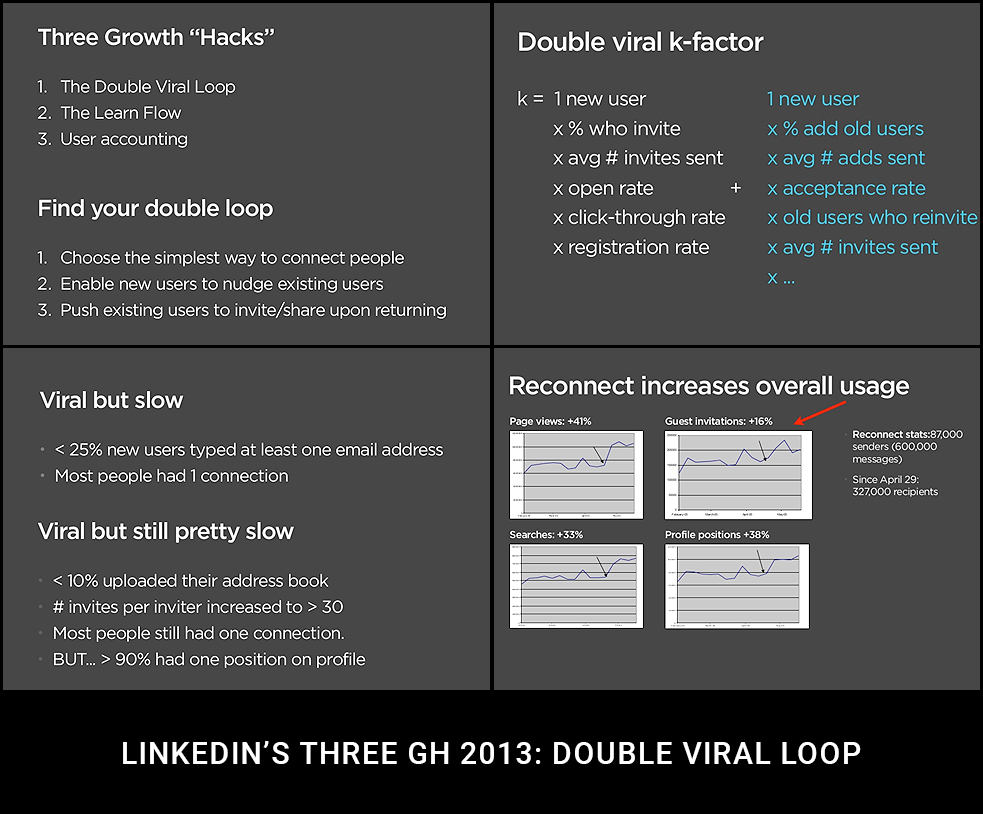

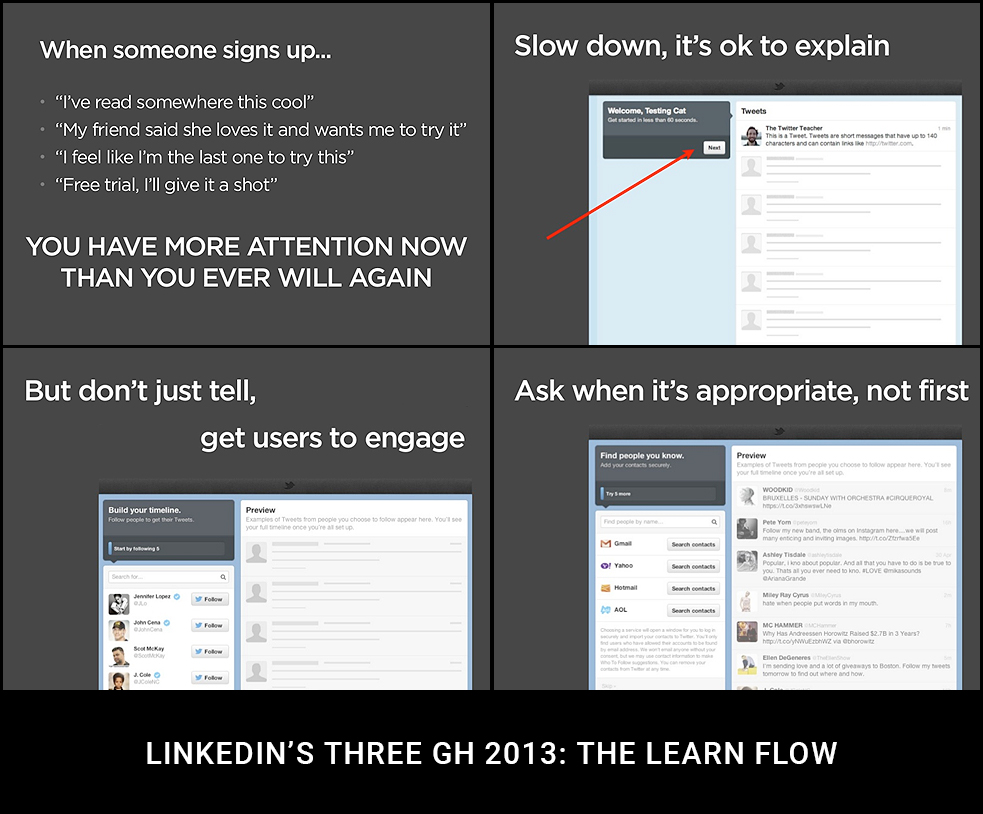

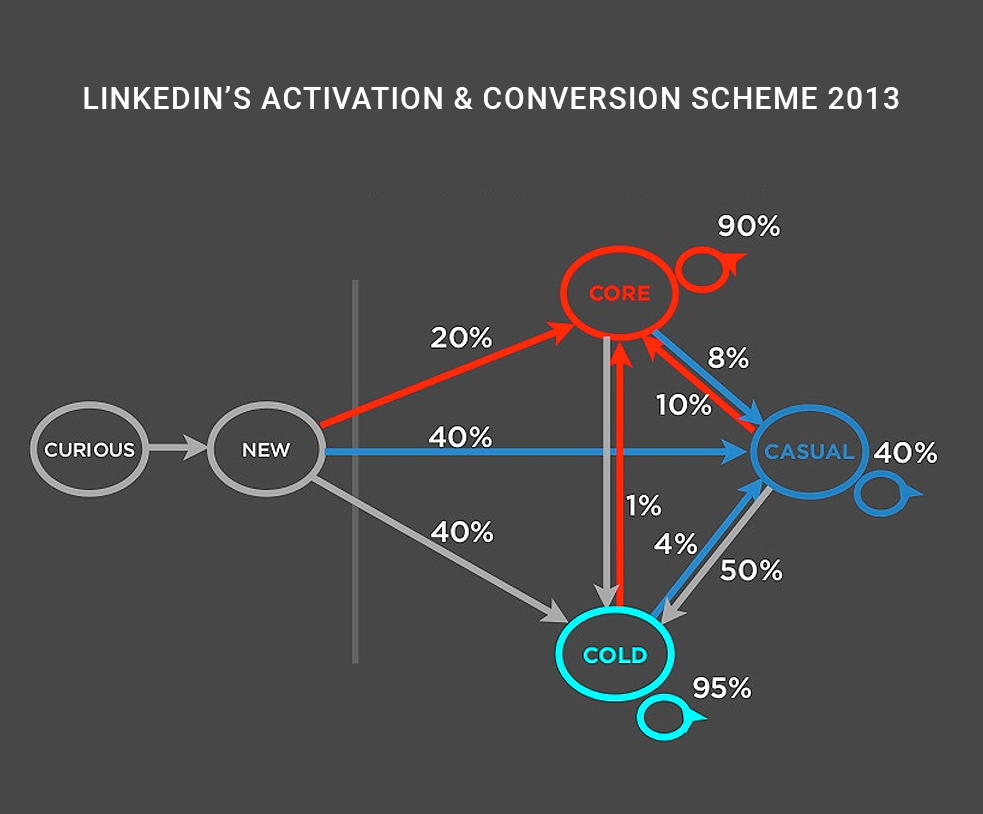

Also new in 2006 was LinkedIn’s fifth growth hack: the double viral loop. Officially, that hack existed as two new features: "Recommendations" and "People You May Know." Basically, every time people signed up for LinkedIn they gave their current company and title. Once new users signed up, they received a list of people at their current (and ex) company already on LinkedIn and the question, "Who do you know?" Connecting was as simple as going through and checking boxes.

As more people joined and sent invitations to connect, current (though perhaps unengaged) users were brought back to the site, at which point they too were prompted to invite and connect with others.

The process above was dubbed the "double viral loop" growth hack since. New users invite more new users and also engage old users (who go on to ask new users themselves.) Therefore, we get two viral loops happening at once.

After a bit of success from this feature, LinkedIn went back in and added another question into the new user flow, this time asking where they used to work. Again, new users got a list of potential connections from their former companies. Hoffman applied to this growth hack methodology again when the "Endorsements" feature debuted in 2012, as yet another way that new and active users can help reactivate their unengaged connections.

The sixth growth hack of LinkedIn’s marketing engine is a delayed monetization. Hoffman was a huge believer in obtaining one million users, getting them engaged, and only then building a business model on top of that. That’s precisely why the company started from free sign-ups and had kept the "freemium" model since its release in 2005.

Technically, LinkedIn kicked off their monetization efforts with Adbrite ads in mid-2004. The returns on these ads was insignificant, however, and it wasn’t until 2005 that LinkedIn launched three more lucrative revenue streams: job listings, subscriptions, and advertisements. It was no coincidence that they achieved profitability in 2006.

LinkedIn’s seventh growth hack is very enlightening and permeates all aspects of the startup’s strategic and tactical growth; it’s about focusing on developing strengths rather than improving weaknesses.

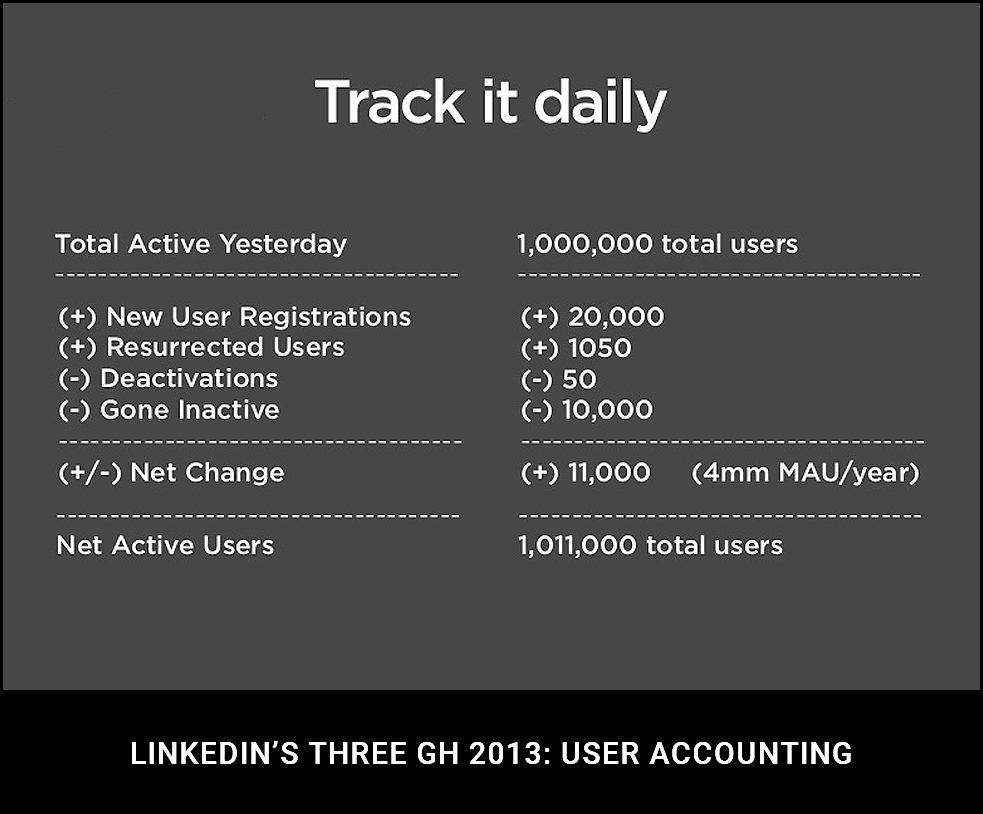

As it was driving 40% of signups by 2008, the LinkedIn homepage was already a particular strength for the company, whereas email invitations could account for just 4% of growth. Data indicated that people who arrived at the site organically visited, on average, 30 pages per session, whereas people coming through an invite visited 10 pages per session. Ergo, invites were not attracting engaged visitors, and therefore would not be a big, successful channel, regardless of how they grew it.

Understanding that LinkedIn was already doing an excellent job with users arriving at the homepage organically, they chose to double down on this group by removing as much friction as possible from their user experience.

LinkedIn was able to grow in four months almost the same number of signups from homepage improvements as they did over two years of optimized email invites. Of course, a near doubling of the effectiveness of email invites is nothing to look down one’s nose at but these numbers do indicate that when looking for significant gains in a relatively small timeframe, focusing on improving strengths presents a much more powerful opportunity for growth.

Finally, another example of playing up strengths comes from LinkedIn’s "Who’s Looked at Your Profile" emails. The emails had a 5% CTR (Click-Through Rate) for inactive users, but a 20% CTR for active users. Rather than trying to woo inactive users, LinkedIn chose to once again focus on their strengths, making the emails more appealing to active users by testing subject lines, copy, and formatting. In this manner, that seventh growth hacks mean that it is easier to get an active user to do a lot more than to get an inactive user to do anything.

Sign up for updates

Subscribe for free with your email to receive lean hints and marketing insights!

OK, SUBSCRIBE ME